The Us Should Institute Taxpayer-funded Paid Family Leave.

Leap to a department of this report:

![]()

![]()

![]()

A growing share of working parents and an aging population take put force per unit area on more than American workers as they residual family caregiving responsibilities and work obligations. Amid these changes, the issue of paid family unit and medical leave has captured the attention of policymakers and advocates across the political and ideological spectrum.

A growing share of working parents and an aging population take put force per unit area on more than American workers as they residual family caregiving responsibilities and work obligations. Amid these changes, the issue of paid family unit and medical leave has captured the attention of policymakers and advocates across the political and ideological spectrum.

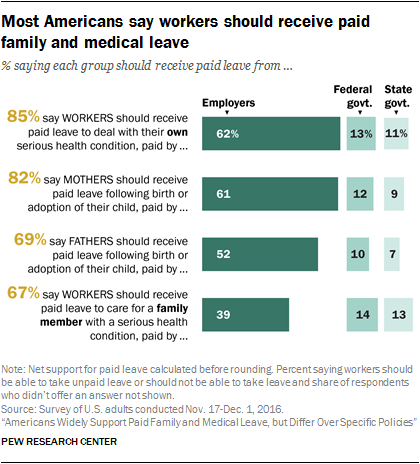

A new study conducted by Pew Enquiry Center finds that Americans largely back up paid exit, and most supporters say employers, rather than the federal or state regime, should cover the costs. All the same, the public is sharply divided over whether the government should require employers to provide this do good or allow employers decide for themselves, and relatively few see expanding paid leave as a top policy priority.

While majorities of adults express support for paid exit for mothers and fathers after the birth or adoption of their child, as well as for workers who need to treat a family member with a serious health condition or to deal with their own medical bug, support is greater in some cases than in others. Virtually eight-in-x Americans (82%) say mothers should have paid maternity go out, while fewer (69%) support paid paternity leave. And those who favor paid maternity and paternity leave say mothers should receive considerably more time off than fathers (a median of 8.6 weeks off for mothers vs. 4.3 weeks for fathers).

There is also broader support for paid go out for workers dealing with their own serious health condition (85% say workers should be paid in these situations) than at that place is for those caring for a family fellow member who is seriously ill (67% favor paid exit for these workers).

There is also broader support for paid go out for workers dealing with their own serious health condition (85% say workers should be paid in these situations) than at that place is for those caring for a family fellow member who is seriously ill (67% favor paid exit for these workers).

The wide-ranging study of public attitudes about paid family and medical go out also included well-nigh 6,000 interviews with Americans who have recently taken leave (or were unable to take leave when they needed or wanted to do and so), in order to reflect direct personal experiences as well as policy views. The survey finds that 64% of those who took leave in the past ii years say they received at least some pay during their time off. A large majority of them (79%) say that some or part of that pay came from vacation days, sick exit or paid fourth dimension off (PTO) they had accrued prior to their exit. Only 20% of those who got paid – or 13% of all "leave takers" – say they had access to family and medical go out benefits paid by their employer.

Note on terminology

Throughout this study, when referring to attitudes toward paid leave policies, the terms "family unit and medical leave" or go out from work for "family or medical reasons" refer to time off following the birth or adoption of i'due south child, to treat a family member with a serious health condition, or to deal with 1's serious health status.

In order to distinguish between the experiences of those who took time off from work (or who needed or wanted to take time off simply were unable to do and so) under different circumstances, the term "parental leave" refers to taking time off from work following the nascency or adoption of a child; "family leave" refers to taking at to the lowest degree v days off from work to care for a family member with a serious health condition; and "medical go out" refers to taking at least five days off from work to deal with 1'due south ain serious health condition.

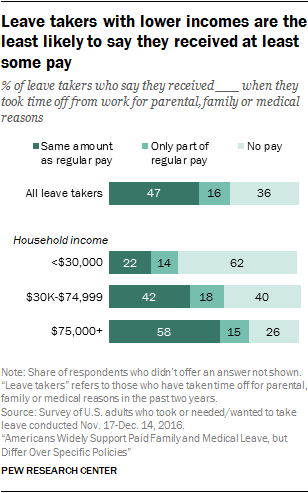

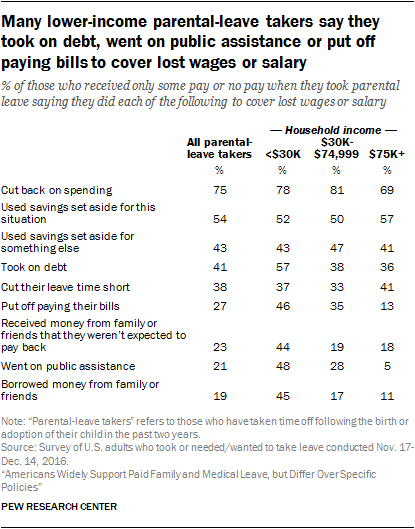

The study reveals a sharp income divide in the way workers navigate these situations. Center- and higher-income leave takers are much more probable than their lower-income counterparts to have access to paid time off – whether through a specific employer-provided paid leave benefit or by using accrued time off. Six-in-ten leave takers with household incomes between $xxx,000 and $74,999, and an even higher share (74%) of those with incomes of $75,000 or more, say they received at least some pay when they took time off from piece of work for family unit or medical reasons. In contrast, only 37% of get out takers with annual household incomes nether $thirty,000 say they received pay. Many lower-income leave takers say they faced difficult financial tradeoffs during their time abroad from work, including 48% amidst those who took unpaid or partially paid parental get out who say they went on public assistance in order to cover lost wages or salary.

The need for family and medical exit – whether paid or unpaid – is broadly felt across the United States. Roughly six-in-ten Americans (62%) say they accept taken or are very probable to accept fourth dimension off from work for family or medical reasons at some point. Among adults who take been employed in the past two years, virtually a quarter (27%) say that they took time off during this period following the nascence or adoption of their child, to intendance for a family member with a serious health status, or to deal with their own serious wellness condition. In add-on, 16% of Americans who were employed in the past 2 years report that there was a time during this period when they needed or wanted to accept time off from work but were unable to exercise so.

The need for family and medical exit – whether paid or unpaid – is broadly felt across the United States. Roughly six-in-ten Americans (62%) say they accept taken or are very probable to accept fourth dimension off from work for family or medical reasons at some point. Among adults who take been employed in the past two years, virtually a quarter (27%) say that they took time off during this period following the nascence or adoption of their child, to intendance for a family member with a serious health status, or to deal with their own serious wellness condition. In add-on, 16% of Americans who were employed in the past 2 years report that there was a time during this period when they needed or wanted to accept time off from work but were unable to exercise so.

Those who weren't able to accept leave when they needed or wanted to tend to exist among the nation's lower-income workers. Amidst adults employed in the past two years with almanac household incomes under $30,000, three-in-10 say they were unable to take leave when they needed or wanted to at some point in the past ii years. By comparison, only 14% of those with incomes of $30,000 or more than fall into this category. Across income groups, those who didn't take fourth dimension off when they needed or wanted to cite financial concerns more any other reason when asked why they didn't take time off from piece of work when they needed or wanted to; about seven-in-10 (72%) say they couldn't beget to lose wages or salary. This is also the reason cited most oft by those who were able to have some time off simply wish they had taken more.

These findings are based on ii nationally representative online surveys conducted by Pew Research Center with support from Pivotal Ventures: i a survey of ii,029 randomly selected U.S. adults conducted Nov. 17-Dec. 1, 2016, and the other a survey of 5,934 randomly selected U.S. adults ages xviii to 70 who have taken – or who needed or wanted but were unable to have – parental, family unit or medical leave in the by 2 years, conducted Nov.17-Dec.14, 2016. 1

The written report as well finds that adults who are employed or looking for piece of work value flexibility as much as they value having paid family or medical get out. When asked what benefits or piece of work arrangements assist them well-nigh or would assistance most personally, almost every bit many cite being able to choose when they piece of work their hours (28%) as cite having paid family unit or medical leave (27%); almost 1-in-five (22%) say having flexibility to piece of work from dwelling house would aid them the most.

However, amongst those who accept taken go out in the past two years or take needed or wanted to do so, having paid leave for family or medical reasons is cited every bit being the virtually helpful more than than any other benefits or piece of work arrangements. About four-in-ten (38%) in this group bespeak to paid family or medical go out, while the second-most cited item – having flexibility to choose their schedule – is seen as about helpful by 24% of those who take taken get out or needed or wanted to do so in recent years.

The changing demographic landscape in the U.South.

The long-term ascent in U.Southward. women's labor strength participation, particularly among mothers, has led to an increasing share of infants living in homes where all parents are working. In 2016, 50% of children younger than ane year of historic period were living in such an arrangement – twoscore% with two working parents and 10% with a single working parent. Thirty years before, this share was 39%; and in 1976, simply 20% of infants were living in a home where all parents were working.

Meanwhile, as the elderly population in the U.S. continues to abound, the number of people involved in informal caregiving of older adults is expected to rising. About 15% of the population was ages 65 or older in 2015, and projections propose that by 2050 about one-in-five (22%) Americans will fall into this category. These older people are more likely to exist employed than in the past; in 2016 virtually one-in-5 people ages 65 or older were withal working, upwardly from 12% in 1980, according to Pew Research Center analysis of Electric current Population Survey data.

In recent years, 25 million working people reported that they provided unpaid care to someone with an aging-related status in the previous iii to 4 months – sixteen% of the employed civilian population in the U.S., according to Agency of Labor Statistics (BLS) American Time Employ Survey information. And for some people family caregiving is a multigenerational try. A 2015 Pew Research Eye survey found that nigh half (47%) of adults ages xl to 59 had at least one parent ages 65 or older, and were as well either raising a child younger than xviii, or had given fiscal back up to an developed kid in the by year.

More than than ever, caregiving responsibilities extend to both women and men. While in 1965 married fathers living with their children spent about two.5 hours a week on child care, that number rose to seven hours a week by 2015. In comparison, moms spent most 15 hours a calendar week caring for their child in 2015. And when it comes to providing care for older adults, men and women are similarly likely to have done so in the prior three to four months. Among the employed civilian population, most 15% of men say every bit much, as do 18% of women, according to the BLS.

Most supporters of paid leave say pay should come up from employers rather than from state or federal government

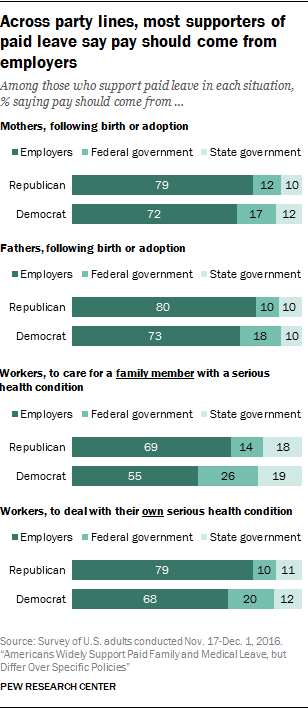

About three-quarters of Americans who support paid leave for mothers (74%) or fathers (76%) following the birth or adoption of a child say pay for time off should come up from employers, and a similar share (72%) of those who favor paid medical leave for workers with a serious health condition say the same. When it comes to who should comprehend the cost of paid exit for workers when they take time off to treat a family unit fellow member with a serious wellness status, a smaller majority (59%) of paid-leave supporters say pay should come from employers, while about two-in-ten say it should come up from federal (22%) or state (twenty%) government.

About three-quarters of Americans who support paid leave for mothers (74%) or fathers (76%) following the birth or adoption of a child say pay for time off should come up from employers, and a similar share (72%) of those who favor paid medical leave for workers with a serious health condition say the same. When it comes to who should comprehend the cost of paid exit for workers when they take time off to treat a family unit fellow member with a serious wellness status, a smaller majority (59%) of paid-leave supporters say pay should come from employers, while about two-in-ten say it should come up from federal (22%) or state (twenty%) government.

The majority of paid-leave supporters across the political spectrum are more probable to look to employers rather than to authorities to cover the costs of providing this benefit, although Democrats express more support for regime-paid family unit and medical leave than practice Republicans. For instance, about a third (32%) of Democrats who say workers should have paid leave from work to deal with their own serious wellness status say pay should come from either the federal or land government, compared with 21% of Republican supporters of paid medical leave. And while 45% of Democrats who back up paid leave for workers who take time off to care for a seriously sick family member say the government should pay for this benefit, 31% of Republicans who support paid leave for this reason say the same. More pocket-sized merely still meaning partisan differences are also axiomatic on views of who should pay when mothers and fathers accept leave.

Overall, Democrats are more supportive of paid leave than are Republicans and independents, though at least three-quarters of each group say mothers should accept access to paid maternity leave and that workers should be able to take paid exit to deal with their ain serious wellness status. Democrats, Republicans and independents are less supportive of paid leave for fathers and for workers who need to treat a family unit member with a serious health condition than they are of paid maternity and medical leave. Still, most Democrats and independents – and just over one-half of Republicans – limited support for paid leave in each of these two situations.

Overall, Democrats are more supportive of paid leave than are Republicans and independents, though at least three-quarters of each group say mothers should accept access to paid maternity leave and that workers should be able to take paid exit to deal with their ain serious wellness status. Democrats, Republicans and independents are less supportive of paid leave for fathers and for workers who need to treat a family unit member with a serious health condition than they are of paid maternity and medical leave. Still, most Democrats and independents – and just over one-half of Republicans – limited support for paid leave in each of these two situations.

Women and young adults besides generally express more support for paid go out than do men and those ages 30 and older. For example, 82% of adults ages xviii to 29 say fathers should be able to accept paid get out post-obit the nascence or adoption of their child, compared with 76% of those ages xxx to 49, 61% of those fifty to 64, and 55% of adults 65 and older.

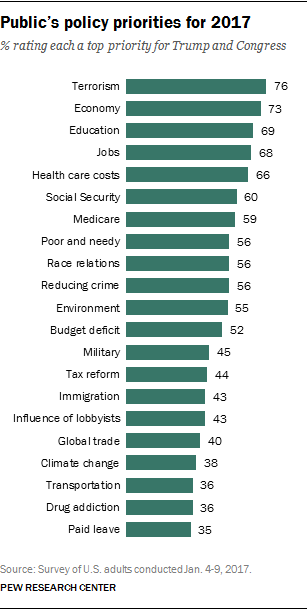

Despite the broad support for paid leave, a Pew Research Heart survey conducted Jan. iv-nine, 2017, about the public'due south policy priorities for President Donald Trump and Congress in the coming year finds that relatively few Americans (35%) see expanding access to paid family unit and medical get out as a top policy priority. In fact, expanding access to paid family and medical go out ranks at the bottom of a list of 21 policy items, along with improving transportation and dealing with drug addiction.

Most see at least some benefits for employers that provide paid get out

While Americans tend to favor employer-paid over government-paid go out for family or medical reasons, there is no consensus when it comes to a federal regime mandate: Most equally many say the government should require employers to provide paid leave (51%) as say employers should be able to decide for themselves (48%). Opposition to a federal mandate is highest among those who oppose paid get out; amidst those who support paid family unit or medical get out, including those who say employers should pay, more say the government should crave employers to offer this do good than say it should be the employers' determination.

All the same, regardless of whether they support a federal regime mandate, virtually Americans think employers stand up to benefit from providing paid family and medical leave. About 3-quarters (74%) of the public says employers that provide paid exit are more likely than those that don't to attract and keep good workers; 78% of those who favor a government mandate and 70% of those who say employers should decide for themselves share this view.

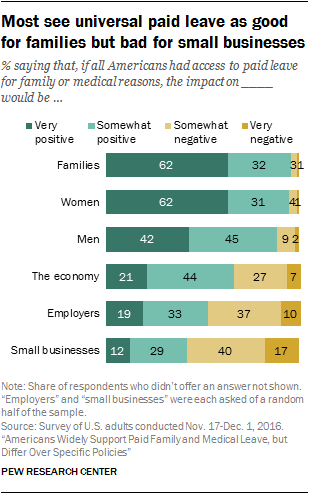

Assessments of the overall touch of paid family and medical leave on employers are more mixed: 53% say universal access to paid leave would take a positive touch on employers, while 46% say the overall bear on would be negative. When asked specifically nearly the impact on small businesses, the balance of opinion is incomparably negative. Roughly vi-in-x Americans (58%) say that universal access to paid go out would take a very or somewhat negative impact on small businesses, while 41% think the impact would be generally positive. By comparing, in that location is significant consensus around the potential benefits to women and families, with near 6-in-x Americans expecting "very positive" results. Overall, virtually two-thirds or more than say the bear upon of universal paid get out on families (94%), women (93%), men (88%) and the economy (65%) would be at least somewhat positive.

Assessments of the overall touch of paid family and medical leave on employers are more mixed: 53% say universal access to paid leave would take a positive touch on employers, while 46% say the overall bear on would be negative. When asked specifically nearly the impact on small businesses, the balance of opinion is incomparably negative. Roughly vi-in-x Americans (58%) say that universal access to paid go out would take a very or somewhat negative impact on small businesses, while 41% think the impact would be generally positive. By comparing, in that location is significant consensus around the potential benefits to women and families, with near 6-in-x Americans expecting "very positive" results. Overall, virtually two-thirds or more than say the bear upon of universal paid get out on families (94%), women (93%), men (88%) and the economy (65%) would be at least somewhat positive.

The public as well makes a distinction betwixt employers in full general and pocket-size businesses in assessments of the trade-offs they may need to make in order to provide paid family and medical leave. About six-in-ten (59%) say well-nigh employers that provide paid leave can beget to do and so without reducing salaries or other benefits. In dissimilarity, a majority (69%) say most small businesses that offering paid get out have to cut back on salaries and other benefits in order to do so.

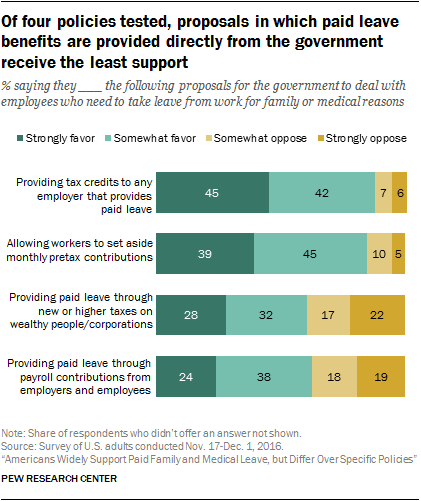

There'south no public consensus on the best policy arroyo for providing paid family unit and medical get out. In general, the public has a more than positive view of policies that incentivize employers or employees rather than those that create a new regime fund to finance and administrate the do good.

There'south no public consensus on the best policy arroyo for providing paid family unit and medical get out. In general, the public has a more than positive view of policies that incentivize employers or employees rather than those that create a new regime fund to finance and administrate the do good.

Some 45% of Americans say they would strongly favor the authorities providing taxation credits to any employer that provides paid leave. And roughly 4-in-ten (39%) express strong back up for allowing workers to gear up aside monthly pretax contributions into a personal account that can be withdrawn if they demand to accept leave from piece of work.

There is less support for a program where the government would provide paid leave to any worker who needs information technology using funding from new or college taxes on wealthy people or corporations – 28% strongly favor this approach. Similarly, 24% strongly favor the institution of a government fund for all employers and employees to pay into through payroll contributions that would provide paid get out to any worker who needed it.

Support for new government programs that would provide paid family unit and medical leave to all workers that demand it is far stronger amidst Democrats than amidst Republicans or independents. Some 44% of Democrats say they would strongly support a government paid leave plan funded by new or college taxes on wealthy people or corporations, compared with nigh a quarter (24%) of independents and simply eleven% of Republicans. And while about a third (34%) of Democrats express strong support for a government paid exit fund that all employers and employees would pay into through payroll contributions, smaller shares of independents (20%) and of Republicans (xv%) say they would strongly favor this approach.

Democrats are also more likely than Republicans or independents to say they would strongly support the government providing tax credits to employers that provide paid family and medical go out: About half (53%) of Democrats express strong support for this approach, compared with near four-in-ten Republicans (37%) and independents (41%).

The vast majority of Americans (85%) say that, if the government were to provide paid family and medical get out, the benefit should exist available to all workers, regardless of their income, rather than being more narrowly targeted to those with low incomes. When it comes to paid parental go out specifically, near three-quarters (73%) believe that if the government were to provide this do good, information technology should exist available to both mothers and fathers.

About seven-in-ten fathers who take paternity leave return to piece of work within two weeks

About seven-in-ten fathers who take paternity leave return to piece of work within two weeks

Most Americans (63%) believe that mothers generally want to accept more fourth dimension off from work than fathers after the birth or adoption of their child, and more say employers put greater pressure level on fathers to return to work quickly (49%) than say mothers face more than pressure (18%) or that both face virtually the same amount of pressure (33%) from employers.

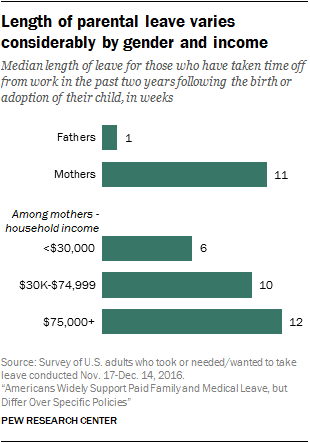

The survey of adults who took leave or who needed or wanted to take leave just weren't able to exercise and so finds that among fathers who took at least some fourth dimension off from work following the nascency or adoption of their child in the past two years, the median length of leave was one calendar week; about seven-in-ten (72%) say they took two weeks or less off from work. In dissimilarity, the median length of motherhood get out was 11 weeks. Among mothers with household incomes under $30,000, even so, the median length of exit was six weeks, compared with ten weeks for those with incomes betwixt $30,000 and $74,999 and 12 weeks for mothers with household incomes of $75,000 or more.

For the most function, mothers and fathers who took parental leave in the by ii years say taking time off did non accept much of an bear upon – either positive or negative – on their chore or career; 60% say this is the case. Still, women are virtually twice as likely as men to say taking time off post-obit the birth or adoption of their kid had a negative impact (25% vs. 13%, respectively).

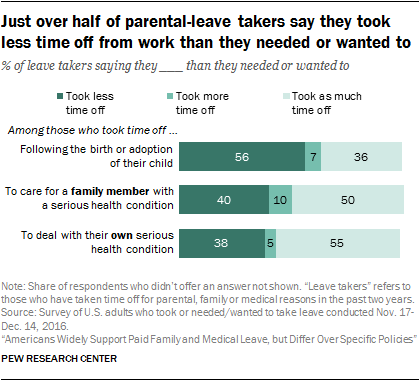

Only over half (56%) of parental-leave takers say they took less fourth dimension off from work following the nascency or adoption of their child than they needed or wanted to, while 7% say they took more fourth dimension off and 36% say they took virtually every bit much time off as they needed or wanted to. Some 59% of fathers and 53% of mothers say they wish they had taken more time off from work than they did following the birth or adoption of their child.

Only over half (56%) of parental-leave takers say they took less fourth dimension off from work following the nascency or adoption of their child than they needed or wanted to, while 7% say they took more fourth dimension off and 36% say they took virtually every bit much time off as they needed or wanted to. Some 59% of fathers and 53% of mothers say they wish they had taken more time off from work than they did following the birth or adoption of their child.

Smaller merely substantial shares of those who took time off from work to intendance for a family unit member with a serious health status or to deal with their own health event also say they took less time off from piece of work than they needed or wanted to have (twoscore% and 38%, respectively).

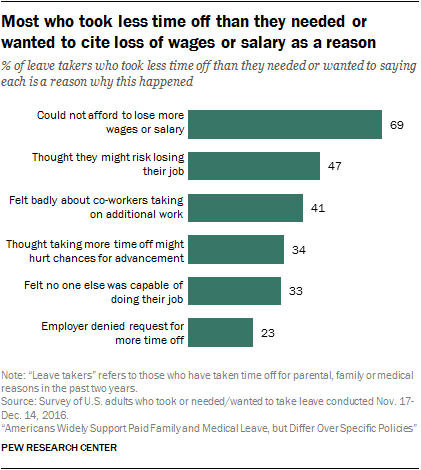

Financial concerns top the list of reasons why those who took leave for parental, family or medical reasons say they took less time off than they needed or wanted to. About seven-in-10 (69%) go out takers who returned to piece of work more rapidly than they would take liked to say they couldn't beget to lose more wages or bacon. About half (47%) say they thought they might risk losing their job, while 41% say they felt desperately about co-workers taking on additional work. Near a third idea taking more than fourth dimension off might hurt their chances for job advancement (34%) or felt that no 1 else was capable of doing their chore (33%). And near a quarter (23%) of those who took less time off than they had needed or wanted to say their employer denied their asking for more time off.

Financial concerns top the list of reasons why those who took leave for parental, family or medical reasons say they took less time off than they needed or wanted to. About seven-in-10 (69%) go out takers who returned to piece of work more rapidly than they would take liked to say they couldn't beget to lose more wages or bacon. About half (47%) say they thought they might risk losing their job, while 41% say they felt desperately about co-workers taking on additional work. Near a third idea taking more than fourth dimension off might hurt their chances for job advancement (34%) or felt that no 1 else was capable of doing their chore (33%). And near a quarter (23%) of those who took less time off than they had needed or wanted to say their employer denied their asking for more time off.

Many go out takers take on debt or apply savings in order to cover lost wages

Most Americans who took time off from work in the past two years for parental, family or medical reasons report that they received at least some pay during this time, with near one-half (47%) saying they received full pay; xvi% say they received just some of their regular pay and 36% say they received no pay at all. Lower-income leave takers, as well equally those without a bachelor's degree, are particularly likely to say they received only some or no pay. For case, among exit takers with household incomes of $75,000 or more, roughly six-in-ten (58%) say they received the same amount every bit their regular pay, while xv% received fractional pay and about a quarter (26%) were not paid. In contrast, just 22% of those with incomes under $30,000 study that they received full pay, while 14% received only some of their regular pay and a majority (62%) received no pay during their fourth dimension off from work.

Get out takers who did not receive their total wages or salary when they took parental, family unit or medical leave say they had to brand sacrifices, such as cutting back on spending, dipping into savings, or cutting their leave short, to compensate for the loss of income. Some, specially those with lower incomes, took more consequential measures, such as taking on debt, putting off paying their bills, and going on public aid.

Get out takers who did not receive their total wages or salary when they took parental, family unit or medical leave say they had to brand sacrifices, such as cutting back on spending, dipping into savings, or cutting their leave short, to compensate for the loss of income. Some, specially those with lower incomes, took more consequential measures, such as taking on debt, putting off paying their bills, and going on public aid.

Roughly 6-in-ten (57%) parental-leave takers with household incomes nether $30,000 who did not receive their full pay when they took time off from work following the birth or adoption of their child say they took on debt to deal with the loss of wages or salary; about half say they went on public aid (48%) or put off paying their bills (46%).

Views of gender and caregiving are related to support for paid exit for new fathers

While most Americans are supportive of mothers and fathers taking leave from work – and receiving pay – following the birth or adoption of a child, many see mothers, and women in general, as more apt caregivers. The survey finds that a majority (71%) of Americans think it's important for new babies to accept equal time to bond with their mothers and their fathers, while about a quarter (27%) think it's more of import to bond with their mothers and just 2% say it's more than of import for them to bond with their fathers. But when it comes to caring for a new baby, more say that, aside from breast-feeding, mothers do a meliorate job than say both mothers and fathers practise about an equally good job (53% vs. 45%); only 1% say fathers do a meliorate job than mothers in caring for a new baby.

The public offers more gender-balanced views when asked who would exercise a better job caring for a family unit member with serious wellness condition – 59% say men and women would practice an every bit good chore. Withal, iv-in-x say women would practice a amend job in this situation (1% say men would).

Older adults and Republicans – especially those who describe their political views as conservative – are particularly likely to say that it's more important for new babies to have more than time to bond with their mothers than with their fathers and that mothers do a ameliorate job caring for a new baby.

Attitudes nigh gender roles and caregiving are linked, at to the lowest degree in part, to views well-nigh the impact of paid leave on men, too as to back up for paid paternity leave. Generally, adults with more than gender-balanced views about mothers and fathers as caregivers for new babies are far more supportive of paid paternity leave than are those who say mothers are better caregivers. Those with more gender-balanced views are besides more likely to say universal paid leave would have a very positive touch on on men.

For example, amid those who say mothers and fathers do virtually an as expert job caring for a new baby, 78% express support for paid paternity leave and half say universal paid get out would have a very positive impact on men. Past comparison, amidst adults who say mothers do a amend job, these shares are 61% and 37%, respectively. Significant differences remain when decision-making for factors such as gender, age and political credo, which are associated with support of paid get out for fathers and the impact of universal paid leave on men in general as well as with attitudes about gender and caregiving.

The remainder of this study examines in greater detail the public's views virtually paid exit as well every bit the experiences of workers who take taken parental, family or medical leave in the past two years. Chapters 1-4 focus on findings from the survey of the general public. Affiliate 1 looks at the public'due south evaluations of different paid leave policies, including who Americans think should be covered as well equally who should pay. Affiliate ii explores assessments of the impact of paid go out on families, the economy, employers and employees. Affiliate 3 looks at workers' assessments of the benefits they receive from their employers and how family and medical leave fits in to the broader benefits landscape. Chapter 4 explores views of gender and caregiving.

Chapter 5 examines the experiences of those who took get out and those who weren't able to have leave when they needed or wanted to do so. It looks at whether or non those who were able to take leave received whatever pay during this fourth dimension and how they coped with the loss of income if they did not receive full pay. It also explores reasons why some people return to work sooner than they wish to afterwards taking parental, family unit or medical leave, and why some aren't able to take time off from work at all when they need or want to exercise so. Finally, Chapter 6 provides some quotes from eight focus groups of recent parental- and family unit-leave takers to illustrate the diverse and circuitous experiences of exit takers.

Other key findings

- Americans express some concern that paid family unit and medical leave benefits can be abused. Some 55% think it is at to the lowest degree somewhat mutual for workers who have access to this benefit to corruption it past taking time off from work when they don't need to; 44% say this isn't especially common.

- Almost workers are at least somewhat satisfied with the benefits their employer provides (69%) and believe their employer cares a great deal or a fair amount about the personal well-being of their employees (66%). These assessments vary considerably past income, however; only about half of workers with household incomes under $30,000 express some satisfaction with their benefits and say their employer cares virtually their employees' well-being, compared with majorities of those with college incomes.

- Three-in-10 leave takers say it was difficult for them to learn about what leave benefits, if any, were available to them when they needed to take time off from piece of work for parental, family or medical reasons, and this is specially the case among those with a high school diploma or less and with lower incomes. Leave takers with lower incomes and those without a bachelor's caste are besides less likely to say their supervisor and co-workers were very supportive when they took exit from work.

- Among those who took fourth dimension off from work to care for a family unit member with a serious health condition in the by two years, women (65%) are far more probable than men (44%) to say they were the primary caregiver. Family unit-leave takers ages 65 and older were more likely than those who are younger to say they were caring for their spouse or partner during this time, while those ages 50 to 64 were particularly likely to be caring for one of their parents.

Throughout this written report, when referring to attitudes toward paid leave policies, the terms "family and medical leave" and "taking time off from piece of work for family or medical reasons" refer to taking fourth dimension off following the birth or adoption of i'southward child, to care for a family fellow member with a serious health condition, or to deal with one's ain serious health condition. In gild to distinguish between the experiences of those who took time off from piece of work (or who needed or wanted to take time off only weren't able to do so), the term "parental go out" refers specifically to fourth dimension taken off from piece of work following the birth or adoption of one's child; "family go out" refers to taking at to the lowest degree v days off from piece of work to intendance for a family fellow member with a serious health status; and "medical leave" refers to taking at to the lowest degree 5 days off from work to bargain with one'due south own serious wellness status.

"Go out takers" refers to those who were employed in the past two years and took time off from piece of work during this time following the birth or adoption of their child, to treat a family member with a serious health condition, or to bargain with their own serious health status. "Paid get out" refers specifically to paid leave for parental, family or medical reasons.

References to whites and blacks include merely those who are non-Hispanic and identify as just ane race. Hispanics are of whatsoever race.

References to higher graduates or people with a college degree comprise those with a available'south caste or more. "Some college" refers to those with a ii-year degree or those who attended college just did not obtain a degree. "Loftier school" refers to those who have attained a high schoolhouse diploma or its equivalent, such as a Full general Education Development (GED) certificate.

Source: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2017/03/23/americans-widely-support-paid-family-and-medical-leave-but-differ-over-specific-policies/

0 Response to "The Us Should Institute Taxpayer-funded Paid Family Leave."

Post a Comment